730824_Sounding Off_360 px width.jpg

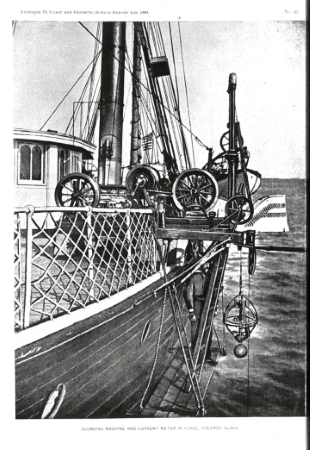

The Sigsbee Sounding Machine, which was used to map the Gulf of Mexico ocean basin in the late 1800's. Credit: NOAA Central Library

In 1875, Navy lieutenant commander Charles Dwight Sigsbee and his ship, the George S. Blake, began a journey into the history books. They started measuring the depth of the Gulf of Mexico with a mechanism that Sigsbee created. When the job was finished three years later, the ship had measured the entire Gulf—the first ocean basin to have an accurate map of all its contours.

Sailors had been measuring depths for centuries. They threw a rope with a heavy weight on the end into the water. Distances were marked on the rope every few feet. Counting the marks revealed the ocean depth.

The technique became known as depth sounding. Crew members would “sound off” the depth as the rope played out. But it wasn’t especially accurate—especially for deep water. But it improved in the mid-19th century. Sir William Thomson of England developed a machine to do the job, using piano wire on a motorized spool.

Sigsbee refined that design. He made the machine larger and more stable, and replaced the piano wire with steel. That improved accuracy. His device became known as the Sigsbee sounding machine. And it was the standard for measuring depths for 50 years.

Scientists named many of the features mapped by the Blake after its commander. So maps of the Gulf of Mexico show the Sigsbee Escarpment, Sigsbee Abyssal Plain, and Sigsbee Deep—the deepest spot in the Gulf—first recorded by Sigsbee’s machine a century and a half ago.