Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

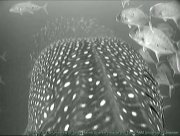

Whale sharks are a bit like pop stars: They attract a crowd. Smaller fish swarm around them. That’s probably a better deal for some fish than others. Sometimes, predators can wolf down entire schools of the groupies in a matter of seconds.

Whale sharks are the largest fish on Earth. They can span 25 feet or more. They’re filter feeders—they filter tiny fish and other small organisms from the water as they swim along with their mouths wide open.

When we talk about “falling asleep,” we don’t usually mean it literally. For Northern elephant seals, though, it is literal—they sleep while falling through the ocean. You can’t help but wonder if they dream about falling, too.

Northern elephant seals live along the coast of California. They can be up to 13 feet long, and weigh a couple of tons. The seals spend seven or eight months a year at sea, foraging for food. They spend the remaining months on shore, where they breed and rest up for the next year’s journey.

The bodies of most fish are scaly. The scales protect them from predators and rough surfaces, improve streamlining, and ward off diseases and parasites. But a few species have different forms of protection: tough skin, bony plates, or thick layers of slime.

Scales vary in size, shape, alignment, and structure. The bodies of most sharks, for example, are covered by rows of tiny, pointed scales that aim toward the tail. The scales of tarpon, on the other hand, are round and can be more than two inches across.

Life in arctic waters is like a giant see-saw. Some species rise to the surface during the day and sink into the depths at night, while others do just the opposite. And the see-saw keeps tottering even during the winter, when there’s no sunlight at all.

But research over the past couple of decades suggests that things could be changing. As the climate warms up, the arctic ice gets thinner. That allows more ships to ply the winter waters. It’s also making it easier to develop the coastline. And all of those ships and buildings are lighting up the night.

The basking shark looks intimidating. It’s the second largest of all fish—it’s 25 feet or longer and can weigh 10,000 pounds. And it can open its jaw a yard wide—wide enough to swallow a person. Yet the shark is a gentle giant. It cruises through the ocean at a leisurely two or three miles per hour, filtering tiny organisms from the water—nothing for swimmers to fear.

Seaweed is useful stuff. Among other things, it provides habitat for fish, turtles, and other creatures.

It’s also used in a lot of products in the human realm: food, fertilizers, animal feed, medicines, thickeners for everything from toothpaste to ice cream, and many more. And there’s one new possible use: providing heat.

Life in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence has been on a seesaw. Some species all but disappeared, allowing others to thrive. Then the seesaw flipped the other way. Some all-but-vanished species tipped up, while the thriving ones tipped down.

In early 1945, as World War II neared its climax, 19-year-old Gore Vidal was the first officer of an Army supply ship in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. The weather was often stormy. Another ship in the fleet was hit by an especially nasty type of wind storm. Vidal wrote his first novel about his time in the Aleutians, and incorporated that storm into the plot. In fact, he named the novel after the wind: Williwaw.

Life always seems to find a way. It inhabits every nook and cranny on Earth, from the upper atmosphere to the rocks below the bottom of the ocean. And even when there’s a disaster, it bounces back—sometimes in a big hurry.

An example comes from a quarter of a billion years ago, after the deadliest known mass extinction. Known as the Permian-Triassic event, it was the result of huge volcanic eruptions. They warmed the atmosphere and made the oceans far more acidic. That killed off most of the life on Earth, including 80 percent of life in the oceans.

In the human world, having “bright eyes” is considered a good thing. It means you’re alert, curious, or energetic—a bright personality with a bright outlook. But in the marine world, bright eyes can be deadly. A critter with bright eyes is easier for predators and prey to spot. That makes it more likely to get eaten, and less likely to catch its own meals.

Some marine creatures have developed a way to hide those bright eyes. A thin glass coating bends and reflects light in a way that allows the eyes to blend into the background.